Reflections on the new ways of working movement

And the case for a 'probiotic education' that helps us digest difficult things and (hopefully) avoid reproducing harm

I’m taking some time off at the moment which has given me an opportunity to zoom out a little and look at the new ways of working movement from another perspective. The inspiration for my reflections comes from literature not within the movement itself, but from adjacent sources. Namely, two books and a documentary, all of which ask uncomfortable questions about the larger societal paradigm we are in – modernity, capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy.

These artefacts have named some concerns and questions I’ve been holding about the movement I’ve been a part of for nearly a decade – one whose mission is to reimagine work in ways that are more free, more human. What I’ve written is my attempt to put a finger on what I’m feeling, what I’m worried about. It might be uncomfortable or provocative to read at times. But my purpose is to contribute to us being more conscious in this business of reinventing organisations, and to point to some potential blindspots that limit us or could even lead to harm.

Hospicing Modernity

The first book I want to share with you is ‘Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism’ by Vanessa Machado de Oliveira (thank you Stefan Morales for the recommendation). I took so many notes because so much of what she writes can be applied almost directly to our purposes.

For example, she writes about the case for academia without arrogance and what that would make possible. If you read the following points outside of the context of academia, though, they make for powerful agreements, almost like a mini manifesto, for a more conscious new ways of working movement:

“We can have conversations that do not reproduce to the same extent the harmful hierarchies of modernity.

We do not idealise or romanticise any discipline or knowledge system.

We can be deeply respectful while also highly sceptical of our own and different worldviews.

We combine relational and rational forms of rigour for better research, teaching, and service.”

For me, what these statements point to is a movement of practitioners that don’t position organisational self-management as a ‘utopia for all’ or force it on the unwilling. We don’t pretend that our prescribed solutions (if we have any) are THE way, or try to do a reductive copy+paste of another organisation’s model (for it can only ever be a snapshot of an evolutionary journey specific to that unique group of human beings). We attend to the relationships and the people, and don’t reduce our organisations to abstractions that can be tinkered with, as opposed to complex systems containing human bodies and feelings.

Doppelganger

“We can have conversations that do not reproduce to the same extent the harmful hierarchies of modernity.” This first point Machado de Oliveira writes keeps coming back to me like a thorny boomerang.

And it leads me onto the second book I’ve read this summer, which is ‘Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World’ by Naomi Klein. The premise of the book starts with Klein being mistaken on numerous occasions for fellow author Naomi Wolf, which leads her down a rabbit hole investigating what could have radicalised her doppelganger, causing her to metamorphosise from feminist into conspiracy theorist. As the book unfolds, Klein ends up exploring bigger themes about ‘the mirror world’ and our shadow selves, the selves we would rather pretend did not exist.

She writes about the different ‘selves’ we construct, like our digital avatars, and how all of these ‘doubles’ are ways of not seeing:

“Not seeing ourselves clearly (because we are so busy performing an idealised version of ourselves), not seeing one another clearly (because we are so busy projecting what we cannot bear to see about ourselves onto others), and not seeing the world and the connections among us clearly (because we have partitioned ourselves and blocked our vision). I think this, more than anything else, explains the uncanny feeling of our moment in history – with all of its mirrorings, synthetic selves, and manufactured realities. At bottom, it comes down to who and what we cannot bear to see – in our past, in our present, and in the future racing toward us…

No wonder we would rather gaze at our reflections or get lost in our avatars, than confront our shadows.”

Exterminate All the Brutes

In ‘Doppelganger’, Klein mentions the HBO documentary ‘Exterminate All the Brutes’ (2021) by Raoul Peck. I watched the four episodes in two sittings with my partner – uncomfortable viewing. Peck asserts that for people in the West, we prefer to think of genocide as beginning, and ending, with the Holocaust. Hitler is our go-to villain, the name we utter when we need a baseline comparison for evil. However, Klein quotes author and politician Aimé Césaire who wrote in ‘Discourse on Colonialism’ that Europeans tolerated “Nazism before it was inflicted on them”, before which, they were wilfully blind to it, because it had been “applied only to non-European peoples” in the form of British colonialism, for example, in Africa and the Americas.

Klein continues: “Césaire was explicit that, in his view, Hitler was not merely the enemy of the United States and the United Kingdom – he was their shadow, their twin, their twisted doppelganger.” Or as Césaire writes himself, we all have a Hitler inside ourselves.

What has this got to do with the new ways of working movement? Well, a few things.

The risk of reproducing harm and re-enacting colonialism

I have seen that it is possible to reproduce harmful hierarchies when we are trying to ‘do good’ by eliminating toxic, top-down hierarchies. This happens either by not being mindful of what we replace the hierarchy vacuum with (see the oft-quoted ‘Tyranny of Structureless’ piece by Jo Freeman in the 1970s, for example), or because power-over (to use Mary Parker Folett’s term) is still being exercised, but under the guise of ‘liberating’ the people or doing something that is so innovative and radical that some will simply not understand, and will become sad but necessary casualties.

After all, Peck tells us in his documentary that some of the hallmarks of colonialism are things like establishing superiority (e.g. Christianity is supreme), re-education, and displacement. Perhaps this sounds extreme, but I want us to be careful when a CEO, for example, has his moment of enlightenment (after reading a book or attending a lecture), declares a new religion (Holacracy, teal, Sociocracy, whatever), initiates a programme of re-education, and eventually exiles those who are unwilling (or unable) to convert.

This is one of the reasons why I like the NER or Krisos models which give employees time to meet with people from other self-managed companies, ask questions, and then take a vote on whether they want to embark on the transformation or not. It only goes ahead if the majority say yes. And they will also become the architects of their own organisation, shaping it from within. This is something so meaningful that when a group of employees from Indaero (an aerospace company Krisos bought in 2023) met together with investors to share reflections from the first part of their transformation journey, many cried tears of joy because they had never felt such sovereignty in their workplaces before.

Another reflection I want to share about colonialism is a worry I have that the new ways of working movement can sometimes by very Eurocentric. Many of the movement’s figureheads are white, European or North American, cisgendered men and so I’m wary of these leaders, or consultants for that matter, ‘teaching’ organisations in the global south how to practice self-management or teal or whatever your term of choice may be. I think Frederic Laloux, author of ‘Reinventing Organisations’, is also aware of this. For example, when invited to Japan some years ago, he (lovingly) rejected the idea of being the authority on ‘teal organisations’ in Japan and suggested instead that there be a ‘Source’ of the teal movement in Japan itself, in a sense, giving his blessing for the movement to take on a life of itself there.

I appreciate Corporate Rebels for profiling organisations around the world, and not just in the West, and sharing their unique models of progressive organising. It’s something I also try to do on my podcast.

Finally, there is also the tricky question: is self-management for everyone? For example, Professor Michael Y. Lee has been researching decentralised ways of organising for several years and in one field experiment, the findings revealed that certain profiles (high performers, those with high self-awareness, high social skills, and an interest in less hierarchical ways of working) thrived when transitioning to self-managing teams, whereas for low performers, it actually degraded their work experience (measured via employee empowerment, job satisfaction and employee engagement).

He acknowledges there were limitations of the study so I’m mindful of drawing too many conclusions from one case study. However, having spoken to and worked with hundreds of people working in self-managing organisations over the last eight years, I have noticed similar patterns myself.

The paper concludes:

“If work is taking place in increasingly decentralised contexts, and this relaxing of constraints systematically favours high performers over low performers, then at a societal level, the trend towards greater decentralisation represents another mechanism of growing inequality in employment outcomes.”

How then can we be more conscious and considered about how we approach organisational transformation, so that we don’t unwittingly reproduce the kind of harm we are trying to avoid?

Different dimensions of organisational transformation

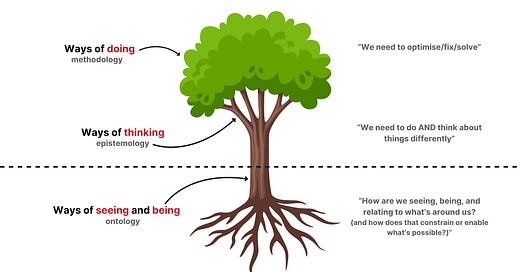

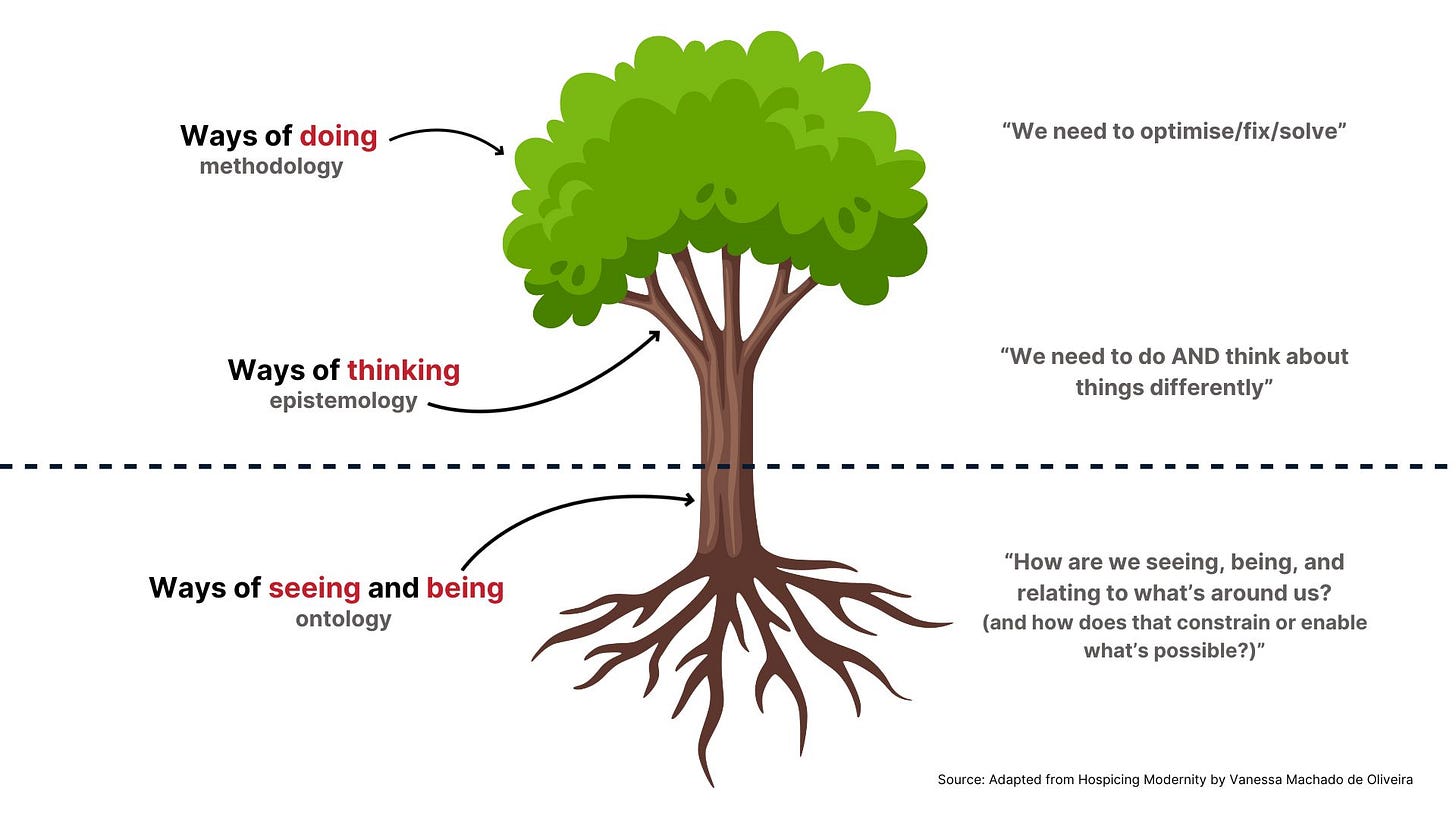

Returning to ‘Hospicing Modernity’, Machado de Oliveira offers the metaphor of an olive tree as a way of gesturing towards the different lenses we can use when approaching modernity and the complex challenges we are currently facing.

I have simplified and adapted it below for the purposes of this post.

What I see is that many organisations are stuck at the level of methodology or ‘doing’ (represented in the metaphor by the leaves and flowers of the tree). In this mode, we our current way of operating as being basically fine – we just need to make some tweaks and adjustments here and there. Machado de Oliveira writes that at this level we might ask questions about the ‘what’ and the ‘how.’

An example might be a traditionally structured organisation deciding to implement something like Agile processes (perhaps ‘squads’ from the mythical Spotify model!) because they want to reap the potential benefits of being more agile, reducing waste, becoming more innovative and so on.

Well-intentioned, perhaps, but the impact will be limited. (Also, if this is implemented top-down, it could even do harm. For example, people feeling an increasing sense of disempowerment as yet another change initiative is being rolled out.)

Then a bunch of organisations may go deeper and explore the next level (epistemology, represented by the tree’s branches), recognising that maybe we don’t only need to do things differently, we also need to think about them differently. Here, Machado de Oliveira suggests, we might ask questions also about the ‘who’ and the ‘why’ (as well as the ‘what’ and the ‘how’.)

An example at this level might be an organisation that has read about the Advice Process (I quite like this page put together by Extinction Rebellion about it) and decided they want to experiment with it because they see value in everyone having more power and authority to make decisions and take responsibility. However, they quickly run into all sorts of problems such as individuals not seeking advice from a sufficient number of people who will be affected by the decision or have relevant expertise. Or a founder who becomes reactive and overrides the decision-maker, thus undermining the whole initiative and damaging trust.

Going deeper

And this is where the next level down comes in. The trunk and roots of the tree (partly visible, partly invisible) are what Machado de Oliveira labels ‘ontology’, or ‘ways of being, desiring, hoping, relating, and existing in the world.’ I have chosen to describe this level as ‘ways of seeing and being’, partly inspired by a rich conversation I had with the founders of Harmonize, Tamila Gresham and Simon Mont.

At this level, to use Otto Scharmer’s metaphor, we must invent a new kind of telescope – one that helps us see the blindspots of the person who is doing the observing, the thinking, the doing. Machado de Oliveira offers some questions in the book, what she calls ‘hyper-self-reflexivity questions’, to support us in this work.

I offer a few of them here as reflection questions we might use to conclude this blog:

“To what extent are you reproducing what you critique?

To what extent are you avoiding looking at your own complicities and denials, and at whose expense? How do you face responsibility for the ways the current system grants you unearned advantages?

Who or what is this really about? How does integrity manifest in your work?

How wide is the gap between where you think you are at and where you are actually at? Who would be able to help you realise that? Would you be able to listen? To what extent can you respond with humility, honesty, humour, and hyper-self-reflexivity when your work or self-image is challenged?

What would you have to give up or let go of in order to go deeper?”

And I might add a few questions of my own, based on what I have written about in this blog:

Who are your doppelgangers? The ‘selves’ you have that you would rather not see?

What is the cost of you not seeing, or integrating, those selves?

If you accept that we all have within us a (potential) Hitler, what learning could this open you up to?

For example, I sometimes say to leaders in my workshops: “If you think you are already empowering, you have closed yourself off to learning. Instead, assume you are a dictator and ask people around you for ruthless feedback. Ask them, for example, when they experience you as dominating and what that looks like. Then you might start to open up genuinely honest dialogues and reveal your learning edges.”

Closing thoughts

When listening to Machado de Oliveira on The Great Simplification podcast, she joked that she often says to people that if they are looking for mastery, certainty and control, “don’t read my book!”

I would argue the same applies to embarking on a journey of exploring new ways of working. If you are looking for mastery, certainty and control, don’t do it!

Machado de Oliveira talks about the need for what she calls ‘probiotic education’, as opposed to our traditional education system which is built around dopamine hits and achievement. Probiotic education is about learning the capacity to confront and sit with things that are hard to digest. And also to compost the shit we have contributed to making!

In the podcast episode, she talks about her Compass Towards Wisdom which includes four capacities:

Emotional sobriety – the ability to interrupt socially conditioned compulsions (for example, I think about examples where organisations try self-management, it doesn’t go as planned, and the founder/CEO quickly aborts the experiment, declaring: “I knew it! People want to be told what to do after all!”, rather than pausing a moment, noticing the affective responses to lack of control or certainty, and choosing to reflect with others on what this means and what choices we might explore)

Relational maturity – the realisation of how interconnected we are, unlike the ‘teenage state’ that Western society is in, and the responsibility that we can own once we accept that (which reminds me of a quote I like that defines leadership as: seeing oneself as the source of what’s around you)

Intellectual discernment – being able to ‘defract ourselves’ and see multiple layers (Machado de Oliveira has a lovely metaphor here of the bus within us and being able to notice the different feelings and perspectives of different passengers without judgment or immediate action), as well as being able to develop the stomach to digest and compost ‘the shit’!

Intergenerational responsibility – what in a crisis moves you to do what’s needed versus what’s in your self-interest? How might we act in and think about our organisations (and society in general) if we truly considered what was needed to cultivate the next generation of leaders (with a lower case ‘l’)?

Machado de Oliveira also jokes about needing an A.A. for humanity. Similarly, Frederic Laloux has talked about the need to support people with ‘growth pain’ in a self-management process, and that you might create a space similar to an A.A. meeting for middle managers, for example, where they process their identity crisis. It’s not easy, this work!

All of this has made me reflect on my role in the new ways of working movement. And it’s a bit of a paradox.

On the one hand, I am helping to gesture towards the beautiful possibilities of exploring ways of working that are less hierarchical and more human. To make this path accessible to anyone who wishes to take it. Sharing examples and stories that show the incredible human growth and flourishing that can occur.

And on the other hand, I want to signpost the potential risks, dispelling the idea of a self-management utopia, trying to normalise the ‘growth pain’ that is required in such a process, and even attempting to scare away those who might underestimate what’s needed, lest they do more harm than good. And I want us to wrestle with uncomfortable questions and call each other out if we start to to become attached to our own dogma at the expense of learning and actually doing some good.

💯 ooh Lisa I love this so much; thanks for taking the time to reflect, integrate, synthesize, and share: what a gift. I love Machado de Oliveira's questions for self-reflection, and the ones you add (the doppelganger one hits hard): uncomfortable even to read, which is a good sign that you/she are on the right track 😬.

very resonant with my own feelings here; I really appreciate you weaving your sources/inspiration and bringing in your own voice; would love to be in dialogue with you (and others!) around navigating this inquiry.

Lisa - I love, love the way you wrapped several powerful topics in one post that is filled with so much richness, deeper contemplation and much needed hyper-self-reflexivity. It is necessary and critical that “we” sit in the overwhelm to sift through our layers of complexities and complacencies. Thank you 😊 so much 🙏🏾!