How to get started with transitioning to a self-managing organisation

Some considerations for beginning the transformation journey

In my previous post I wrote about how self-managing organisations are not for everyone, and some prerequisites to consider before embarking on a transformation journey.

Let’s assume you have a decent number of prerequisites in place – how do you then start? This is a question I get asked a lot. Over the years, I’ve gathered various links and resources and principles that I have shared with people, usually in an unsexy Google document. In this post, I’ve tried to flesh out my thoughts a little in the hopes it might help whoever is reading this make a more informed choice about how to start.

First, a caveat. There is no one right way to start. People have different opinions about what works or doesn’t work. And people can also be convinced that what worked for them will therefore work for everyone else.

I am of the mindset that ultimately, you need to decide what feels right for you, and your travel companions, and simply start somewhere. It probably won’t be the perfect place to start, and that’s fine. The process will be nonlinear and will involve you constantly sensing and responding anyway.

So with that in mind, here are some things to consider and some examples of possible starting points.

1. Who decides?

From the top

It might seem like a contradiction, but in many self-managing organisations, it is a top-down decision that starts the transformation process. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, since the CEO/founder/owner has a special role to play, that of Source. Crucial to this is “holding space” for the transformation to unfold, and also to ensure that the organisation doesn’t revert back to its previous form. (You can read more about this in a provocative article by my friend Tom Nixon.)

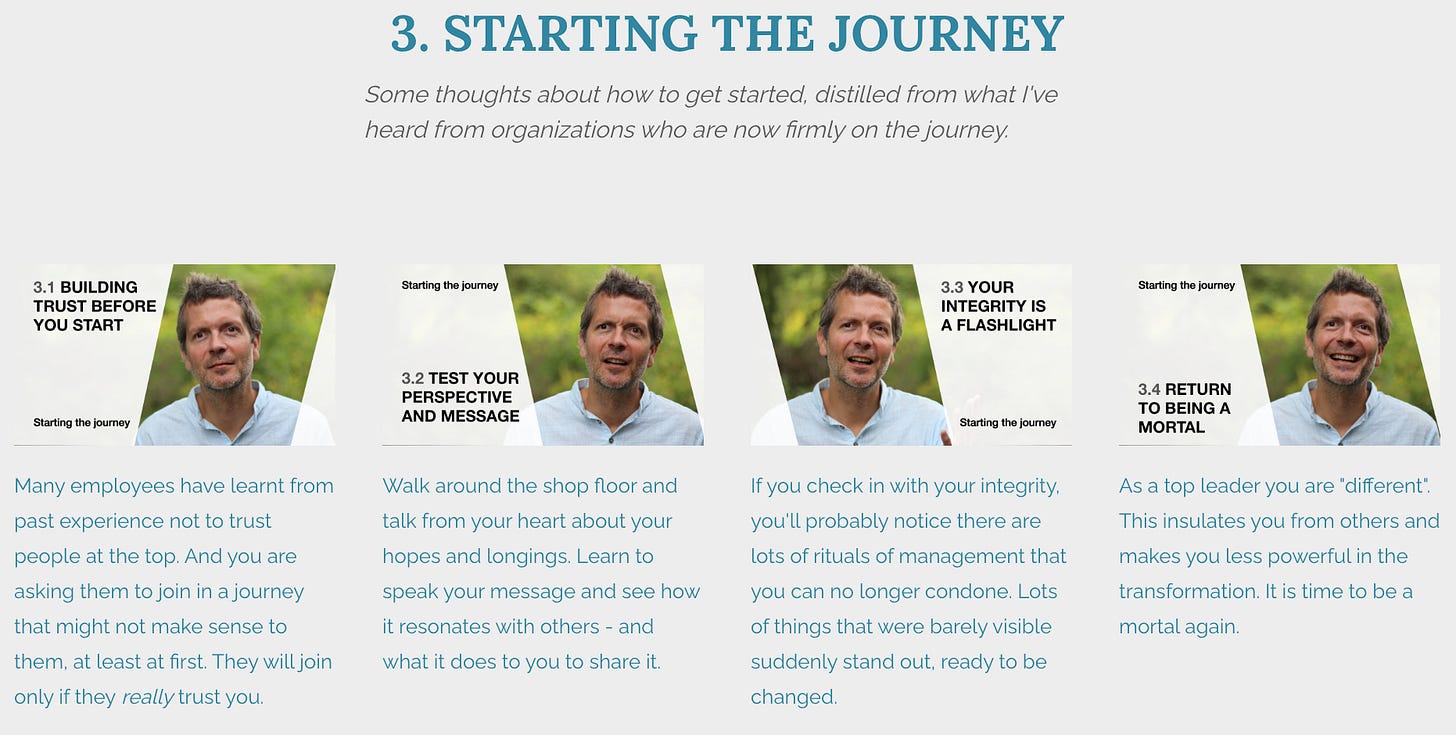

For senior leaders I recommend watching the “Thoughts for top leaders” videos by Frederic Laloux. He has plenty of valuable advice. For example, he says:

“If you're not willing to be changed by the process, don't start… You are both the engine for and the thing that will hold it back.”

He also offers advice on how to introduce and enrol people in the transformation (such as speaking from the heart – “nobody wants to be a concept”).

To be honest, even if you decide to go the route of the organisation deciding, I’d still recommend all senior leaders watch Frederic’s videos. As Isaac Getz wrote in his book “Freedom Inc”, in all the organisations they studied, they found that “the success or failure of the liberation campaign ultimately rested on the shoulders of the [people] at the top.”

From the bottom

Another way to go is to decide in a more democratic way. For example, in the NER approach (which has been responsible for the transformation of 100+ organisations across Spain), the process only goes ahead if 80% of more of the employees vote “yes.” To help them decide, they often visit other NER companies to ask people first-hand about their experience of becoming a self-managing organisation.

It can also be good to give space for people to ask questions, voice concerns and scepticisms before they vote or decide.

Pros and cons

Deciding bottom-up can have its advantages: you can have more co-ownership and buy-in from the start. However, as I touched on in this post, it can be difficult for people to fully know what they’re saying yes to. Even people who vote yes can sometimes change their minds when they see what self-management is actually like in practice, so a democratic decision is not a guarantee of zero resistance!

Deciding top-down is often necessary in larger organisations where a democratic vote might be untenable. For example, see the case of life sciences giant Bayer and its shift towards “Dynamic Shared Ownership.” As one of the “catalysts” driving the change at Bayer put it, right now “one third of the company is excited about and leaning into DSO; one third is hesitant and anxious; and one third is waiting to see what the other two thirds do.” It’s common to have people question the nature of a top-down decision in such a shift, or blame whoever decided when things aren’t working. However, if the person at the top is willing to be humble and change themselves, they can be a powerful lighthouse for change. (One example I love is the story of the owner of a small trades business called Aquadec in Australia and how the resistance started to melt when he dared to be vulnerable.)

2. How far are you ready to go?

If you are a senior leader, it can especially important to think about how far you are ready to go. What aspects of a transformation journey to a more decentralised organisation feel comfortable, what aspects feel edgy, and what aspects are beyond what’s comfortable or imaginable right now? For example, for some groups of people, making salaries transparent feels uncomfortable and unimaginable. Yet, I’ve also known teams who have started with this. So there is no right or wrong. It’s useful to know for yourself because you can then avoid unnecessarily stressing people or promising something you can’t deliver.

I also wrote in my previous post about recommended prerequisites for experimenting with self-managing teams since it seems clear that some struggle more than others. For example, are people confident and competent in their roles? Is there a climate of psychological safety? If the prerequisites aren’t solid, or if you’re a large organisation, you might want to start small.

My colleague Helen Sanderson and I wrote a blog for leaders of nonprofit sector organisations about three possible starting points for exploring more autonomous teams. Having worked in this sector a lot, Helen had hit on small steps and principles that were less controversial and more accessible for organisations where scarce resources and command-and-control legacy cultures often meant people were scared away even just by hearing the term “self-management.”

Three (fairly low risk) starting points are:

Start with three team practices – namely: creating team agreements on how you want to be together; deciding how you will decide (which also means learning new decision making methods, like consent or The Advice Process); and creating granular and transparent roles (which are distinct from traditional job descriptions).

Start with teams working on what gets in the way of them doing their best work – Helen is a big fan of The Ready’s Tension and Practice cards, which name common tensions (such as last of trust, unclear decision-making authority etc.), making it easy for teams to put words to what they are seeing doesn’t work so well. From the team’s top tensions, you can do a 6-8 week “sprint”, perhaps trying out one of the suggested practices outlined in the cards.

Start with a prototype self-managing team – for example, at the Municipality of Slagelse in Denmark with 8,000 employees, Mette Aagaard decided to try the approach of “a coalition of the willing.” Any team that was interested could volunteer to start experimenting. They would then be put in contact with a co-facilitator who would ask some initial questions about why they were interested and their current situation, and finally, they would be encouraged to accept the “startup kit.” This involved one or two team members taking a short online training about the basics of the methodology and then four days in-person training simulating being in a Sociocratic organisation, and how to deal with the challenges of co-leadership that often emerge. After that, the co-facilitator was on hand to support with tailored workshops or support for your team, and teams were also invited to Learning Cafes every month where people could share how it was going, what they were learning, their challenge and so on with others who were experimenting.

Mette’s original goal was to have facilitated three cohorts of the training by the end of 2021, and to have six organisational units working in the new, Sociocratic way. But demand surpassed their expectations – teams got curious as they heard what their colleagues were up to and so the actual number ended up being 15 organisational units and six training cohorts. (You can learn more about this fascinating case in my conversation with Mette here.)

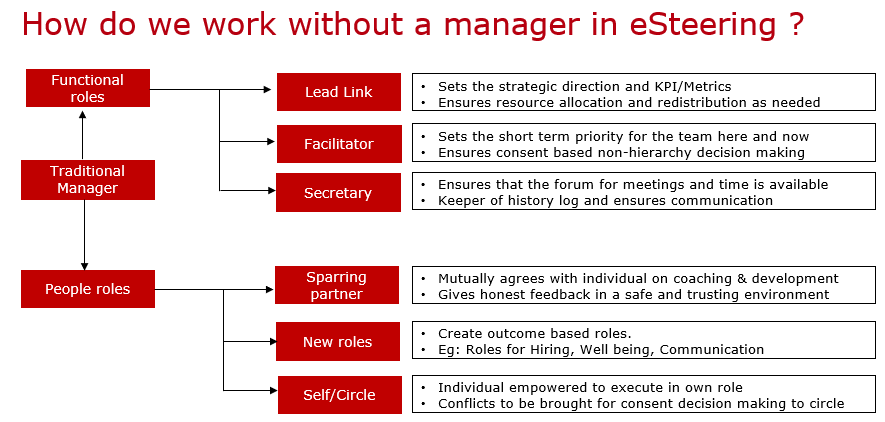

I also like to cite the case of Danfoss Power Solutions. Vivek Menon led the transformation of the eSteering business unit (with around 80 employees), where they documented some of their approaches, such as splitting up traditional manager roles into functional and people roles and distributing them within the team.

Vivek also talked to me about the idea of an “ambidextrous organisation”, since the much larger organisation had no intention of becoming a self-managing organisation. Therefore Vivek’s unit still needed to interface with the rest of the organisation which still functioned as a traditional hierarchy. For me it shows that, especially in large organisations, you don’t necessarily have to go all in. For some departments (like Research and Development), self-management might make sense in terms of agility and innovation, and for others perhaps less so. I’ve also talked to Erik Korsvik Ostergaard about what he refers to as “Teal Dots in an Orange World”, which for many organisations might be a more realistic approach.

So you can think about how far you are willing to go, and also – do you want to go all-in, or start with some “teal dots”? No single approach is necessarily easier or guaranteed to be risk-free, of course, and each brings its own challenges, but it can be valuable to have a sense of the different options and which one feels right for your context at this moment.

3. How do you get started?

We’ve already talked about three possible starting points, but once you start a self-management transformation, it can sometimes feel like pulling on a piece of spaghetti in a bowl and finding everything is entangled!

I find it’s useful to have a bit of an overview of what we are ultimately aiming to transform. Here is where I like to refer to the wisdom of Miki Kashtan. When I interviewed her in 2019, she shared with me three shifts that are needed if we really want to transform our organisations in line with our vision.

The three shifts needed for new ways of working to thrive

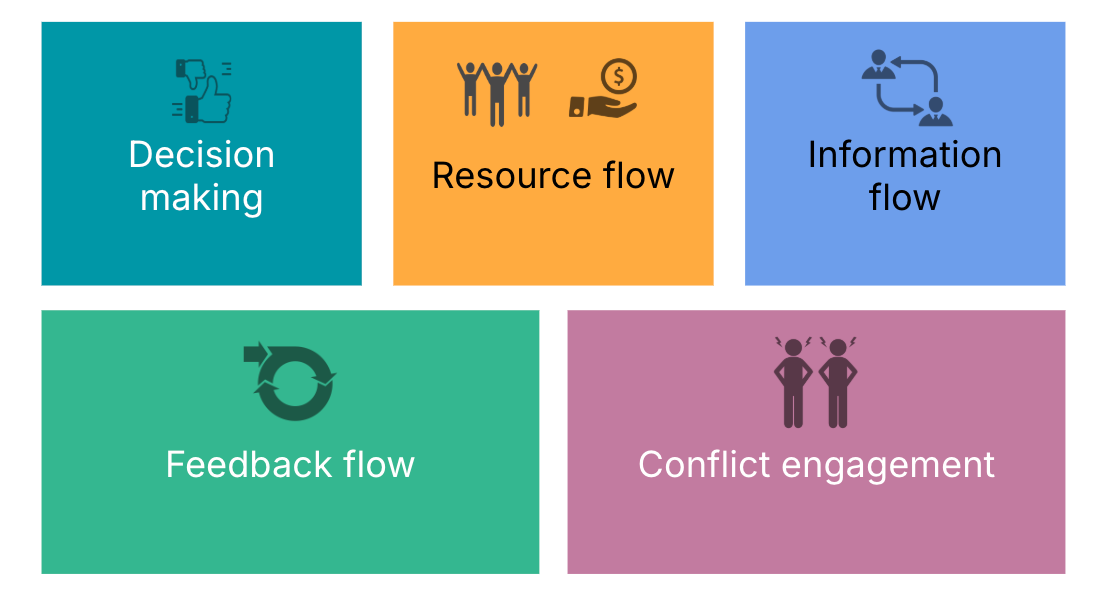

A shift in the five core organisational systems, which are:

Decision-making – Who makes which decisions, using what process, with input from whom, telling whom the result?

Information flow – How does information flow throughout the organisation?

Resource flow – How are resources distributed (financial, human, and otherwise)?

Feedback flow – Who gives feedback to whom, when, and for what specific purpose consistent with purpose and values, or is 'feedback' actually a subtle mechanism for reward and punishment?

Conflict engagement – Is there an established method for attending to conflict? Does the way conflicts are handled support learning and reinforce values?

As Miki puts it, “Any organisation can either express or undermine its purpose and values through the way it sets up its five core systems.” And if we are truly aiming for more participatory, human, decentralised organisations, we will find that if we don’t consciously reimagine these core systems, we will inherit the core systems of the old paradigm.

Most organisations don’t have the capacity to transform all five of these systems at the same time. A more realistic approach might be to choose one or two systems to start with, and to perhaps form working groups of volunteers who will research and craft proposals for how to experiment with, or create agreements for, an alternative approach. You could use a “pilot” or “experiment canvas” which identifies some parameters for the pilot or experiment – Who is working on it and what are their roles? What is our objective? How will we know if it’s successful? When will we evaluate the results? and so on.

An example I like in the ‘Resource flow’ core system is from the self-managing software company, Mindera. To address how to reimagine their salary process, they invested quite a lot of time in workshops surfacing the different needs and ideas. Workshop teams went away and researched possible self-management salary processes and presented them to each other. Eventually, after rounds of feedback, they ended up with a proposal. But there was a snag: around half the people in the organisation wanted full transparency on everyone’s salaries, and the other half were not comfortable with that at all. Rather than favour one need over the other, they devised a solution that integrated both needs: people would see bands of salaries, but not who they belonged to, and a working group responsible for mediating pay rise requests and feedback would be given permission to see everyone’s salaries. (You can learn more about their salary model, and its evolution, here.)

It’s worth noting, you don’t necessarily have to reinvent the wheel with each of these core systems. Many organisations find it helpful to use patterns from self-management systems such as Sociocracy, S3, or Organic Organisation, which give you participatory decision-making protocols or meeting structures, for example, or from other self-management cases, such as The Advice Process, made famous at AES. Or you can “install” a self-management system wholesale, as in the case of Holacracy, where the board, owners, or CEO literally sign over their power to the Holacracy constitution.

What we know from research so far is that it certainly helps to have collective “social practices” in place to support groups not to slide back into the old paradigm, and also to prevent shadow hierarchies or power vacuums from emerging:

“Social practices are script-like descriptions that facilitate shared work (Lee et al., 2020) and they replace traditional management functions – such as decision-making, target setting, feedback, conflict resolution or division of labour – by offering guidelines on how to act collectively in these situations.”

Source: “Leaderless leadership in Radically Decentralised Organisations” by Perttu Salovaara, Johanna Vuori and David Collinson, 2024

Back to Miki’s three shifts

In addition to shifting these five core systems, then, Miki tells us there are two other shifts for us to consider.

An inner shift in those with power (e.g. former managers):

“A person who has structural power needs to transform their habits in order to exercise “power-with”, because otherwise, you will be caught in this very odd, painful contradiction of where you want collaboration, and you want things to go your way...”

This shift involves being open to hearing different needs and perspectives, and crucially being open to something that isn’t what you want! It is a mindset shift, a shift in how we relate, as Miki says, from “power-over” to “power-with.” Or, as my colleagues at Tuff put it, from “parent-child” dynamics to “adult-adult” dynamics. Which also requires developing a bunch of skills that we have not learned in the traditional world of leadership – such as asking coaching questions, instead of always defaulting to giving advice.

An inner shift in those without power (i.e. so-called “individual contributors”):

“The internal change on the part of the person who doesn't have structural power is to overcome fear and habit of deference...”

As I often say when I give talks on this topic: giving people permission to self-organise isn’t enough for them to do it. It takes courage and a climate of psychological safety for people to dare to claim this new-found power, for with it comes exposure and risk.

These inner shifts often invoke what Frederic Laloux refers to as “growth pain”, because we are growing into new versions of ourselves, which often means shedding the comfort and convenience of our previous selves. That’s why, as I wrote in my previous post, I’m such an advocate for intentionally creating systems – coaches, learning and reflection spaces, training – that support people in the inner part of this transformation.

So in terms of getting started, it’s good to know about these three shifts, and consider how you might approach – or at least talk about – each of them.

In summary

Every organisation is unique and there are countless ways to start your journey, but you might want to consider:

Who decides? Will you decide to embark on this process from the top-down, or go for a more democratic decision?

How far are you ready to go? What are the comfortable, edgy and beyond comfortable domains for you? Do you want to go all-in, or start with some low(er) risk experiments or prototype teams?

How will you get started? Which of the five core systems might you want to focus on first? Or do you prefer to use a self-management system like Sociocracy or Holacracy? And how will you approach the dimension of the inner shifts needed?

Finally, I often say to people on this journey: don’t travel alone. I’ve written here about three needs you might have to find your communities when it comes to testing out these new ways of working and sharing learning. There are lots of practitioners out there willing to support you.

I’ve included some resources below that you might like to dive deeper into. Good luck!

Recommended resources

Frederic Laloux has a whole series of videos on “Starting the journey of self-management” here. The whole “Insights for the Journey” is fantastic – if you have a question, it’s probably been answered somewhere in one of his videos!

To learn more about Source work, I recommend my friend Tom Nixon’s book “Work with Source.” Especially if you are a leader or a person initiating a transformation, being a good Source is key.

To learn more about the work of Miki Kashtan and her peers at Nonviolent Global Liberation:

Here’s my interview with Miki Kashtan on the three shifts needed for self-management to thrive

Aligning Systems with Purpose and Values – an overview of the five core systems from the Centre for Efficient Collaboration website, plus four steps for creating alignment

Learning Packets – if you want to go deeper, you con contribute via the gift economy by downloading the detailed learning packets Miki has created, such as this one about the five core systems (and there is also a separate learning packet for each of the systems)